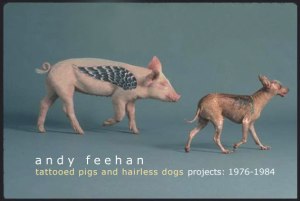

For ten years I had an Obsession. It had nothing to do with Calvin Klein. Driven by a dream I had at the age of twenty-three during my junior year at the University of St. Thomas in Houston, Texas, I began to draw pigs with wings. I drew pigs with wings over and over until, during my senior year, I realized it might be possible to actually create a real winged pig by employing tattoos.

During that same year, I met Bob Wade. Bob came to town as visiting artist at St. Thomas and installed a large and humorous floor piece in the gallery of the Art Department . He needed several hands to help with all the work involved in creating the piece, and, impressed by his sense of the outrageous, I volunteered. Working together on this piece, we got to know each other, and we mulled over my idea to tattoo a pig. I was encouraged. Bob was on the faculty of the University of North Texas, and he suggested that I apply for admission to the graduate school.

I received a two-year teaching fellowship from the University of North Texas, and I moved to Denton in 1975. For another two years I made paintings and prints employing the image of the winged pig, culminating in

the full realization of my dream, a live pig with wings.

*******

Minnesota

Denton, Texas is what anyone would call a college town. Situated a half-hour’s drive north of Dallas, it’s the home of two universities. However, Denton is small enough that you can get in your car and be out in the country in five minutes. In that rural environment it’s very easy to find pigs.

Indeed, finding pigs was no problem. Finding both a tattooist and a veterinarian willing to facilitate the project was another thing altogether. Previously in Houston I had made the rounds to a couple of the old tattoo parlors. In those days they were pretty moth-eaten and cheesey, so I was a bit put off by the general ambience of them to begin with. When I made my pitch, in the most generous and positive terms I could muster, I was told, after a guffaw of disbelief, “NO!” Tattooists were defensive about a lot of things back then, and I think I offended one guy’s sensibilities as an artiste by lowering his art form to the barnyard. Another tattooist was worried about getting busted by the health department if word got around that he was tattooing pigs in his shop. I understood that, because tattooing was potentially a hazard for the proliferation of disease, hepatitis in particular, and in some parts of the world, tattoo shops were illegal for that very reason. The obvious remedy to all this is, of course, a vigorous sanitation regimen, including the use of an autoclave.

I gave up on finding a tattooist in Houston who would be willing to step up to the challenge, but I found a great one in Fort Worth. His name was Randy Adams.

Randy was open-minded enough to listen to what I was saying, and the weirdness of it appealed to him. I had told him that I had a home-made, rather antique and scary tattoo apparatus that a friend had given me, and, concerned that I might let that apparatus fall into the wrong hands…maybe I already had… he agreed to tattoo my pig, even-steven, in exchange for that tattoo apparatus. For my next trick, I had to then find an open-minded veterinarian with a sense of humour.

In Texas, most veterinarians come from Texas A&M. The Aggies are justifiably proud of their Veterinary Medicine program. The Aggies are also traditional and rather conservative.

During my preliminary investigations about different kinds of pigs I realized they came in all sorts of shapes and sizes. For practical reasons I was drawn toward a variety of pig I had read about in the scientific literature called the Hanford miniature. This pig was developed in the state of Washington some years ago as a laboratory animal. A fully grown standard pig is a sizeable creature, sometimes reaching seven or eight hundred pounds, so it became imperative for science to have a much smaller variety, and the Hanford miniature was developed. In researching all this, I soon realized the incredible cruelty that was inflicted on these animals in the name of science. I read about burn research and nuclear radiation experiments. I read about alcoholism studies where pigs were fed ethanol and then killed for liver necropsies. It was a long list. Surely, I thought, in the face of all this, people would not object to my project. What I wanted to do in the name of art wasn’t cruel at all compared to what I saw done in the name of science.

There was, to my pleasant surprise, a small population of Hanford miniature pigs at Texas A&M, so I wrote the chairman of the School of Veterinary Medicine, explaining my project. I received an emphatic negative response. I wish I had kept the letter. It was written in a tone so irate and dismissive that, when I read it, my immediate response was to wad it up and throw it in the trash. Today it would have been an amusing document. As a consequence of this experience, I knew I had to stop telling people in advance about the project, and I knew I had to get a standard-size pig.

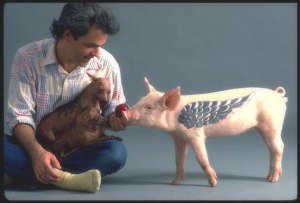

I visited a hog farm right outside of Denton and got a two-month-old Chester White pig. I named him Minnesota.

I managed to overcome my reluctance to convince anyone else of the merits of my project quickly enough to find a veterinarian right in Denton. He was a regular dog-and-cat vet who of course had some experience with other critters, and he, not surprisingly, was also an Aggie. He was willing to be the anaesthetist for a very reasonable fee. Really, he was interested in the idea enough to charge only for his expenses. But he didn’t want to lose his “regular guy” reputation, so he asked to remain anonymous. I understood. He still had a practice to protect (!) I coordinated the tattoo event among all the participants, who were by then: Randy Adams and his assistant, the vet, two photographers (Bob Wade and Burt Finger), a video person, myself, and, of course, Minnesota. We all met on Sunday, November 21, 1976, at the veterinarian’s office.

The entire procedure was painless, completely sterile, and surgically precise. Everybody did a marvelous job, and Minnesota, after going to sleep as just an ordinary pig, woke up as the only winged pig in the world.

That spring my thesis was published. Entitled The Tattooed Pig as an Aesthetic Dialectic, it’s still on file in the Art Department at the University of North Texas.

TWO DIGS AND A POG, OR, WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE?

I feel that I must relate how amazed I was to see that Minnesota had bonded with my dogs, Chester and Elvis, and how much like one of the family he was. Before the tattoo project, I had never spent any time with pigs. I had read of their intelligence,and I knew they could be trained. I ended up raising Minnesota to think he was a dog…he was just a weird-looking dog. He played with the dogs, he ate with the dogs, and he slept with the dogs. Everywhere that the dogs and I would go, Minnesota went also. He learned to ride in the back of my pickup truck just like any other respectable dog. We got a few stares.

In the beginning, our unorthodox domestic arrangement was unacceptable to the landlord, who knew I was an artist, but wasn’t ready for a pig on his property. But by then I had learned to be persuasive in the face of just about any form of antagonism, and besides, Minnesota was just so damned funny, the landlord finally just gave in.

I had no clue at first about how to get Minnesota to behave, but since he bonded with the dogs, he followed their cues. Chester and Elvis weren’t exactly trained per se, but they loved me and usually wanted to do as I said. So, Minnesota was trained by proxy, by Chester and Elvis. They were a pack. During the winter of 1976 and spring of 1977, the three were inseparable. Minnesota made his public debut at the opening of my MFA thesis exhibition at the University of North Texas Art Department on Saturday, January 29th, 1977. He was present in the gallery only at the opening, and he stayed inside a corral made of hay bales and plastic drop cloths on the floor.

After the opening, he came home to his spot in my back yard. In the weeks following Minnesota’s premiere, he tripled in size. He was growing bigger by the minute. It was one of many reminders that my grad school career would soon be over, and it would be time to leave town. So, besides being concerned with finishing my thesis and other related business, I was trying to wrap up everything in Denton in preparation for a new life back in the big city of Houston. I put out feelers trying to find a kind, probably vegetarian, person who would accept the gift of a winged pig… an outright gift on the single condition that this pig never be slaughtered.

Stanley Marsh 3

Before I even exhibited Minnesota at my MFA thesis show, I knew I was going to have to find a home for him, because after graduate school, I planned on leaving Denton. There was, in 1977, a universal ban on swine inside the city limits of every town in America. This was before the popularity of Vietnamese potbellied pigs, and not too many people at that time could conceive of having a pig for a companion. I was faced with the dilemma of finding a home for Minnesota…somewhere that he could spend a long natural lifespan as Art instead of sausage and footballs. Nobody in Denton was interested, but someone suggested I get in touch with Stanley Marsh 3 of Amarillo, Texas. Stanley was known as an”eccentric Texas millionaire” who, besides being a prankster, was the patron of a couple of rather notorious outdoor works of art: the Cadillac Ranch, designed and built by the architectural group known as Ant Farm, and the Amarillo Ramp, the last work of art ever made by Robert Smithson. Smithson in fact was killed at the site of the work when his plane crashed during an observational fly-over. I was hearing a lot of mixed things about Stanley Marsh, but I figured the only way to find out about him was to write him a letter. I did that, proposing that I give him Minnesota in exchange for a promise to let him live to be an old pig.

A few days after I wrote Stanley Marsh, I got a phone call. It was him. In a jocular and complimentary mood, he said that not only would he be delighted to take care of Minnesota for life, he could hardly wait to meet him. My dilemma was solved, I thought. I was happy that Minnesota would have a place in Stanley’s menagerie of odd animals which, he told me, included llamas, yaks, guanacos, peacocks, a zebra named Spot, and a camel named Humphrey who spat at people.

I was also glad to be recognized as an artist by a man who had established a reputation as a patron of Ant Farm, Robert Smithson, and John Chamberlain.

Not even out of graduate school, I was secretly pleased with myself.

In late March, 1977, I drove Minnesota, accompanied by Chester and Elvis, and by my wife at the time, Nancy, to Toad Hall, the home of Stanley Marsh 3, outside of Amarillo, where Minnesota was received by a party of people and animals…Stanley’s family and several friends, and the whole menagerie. It seemed like we’d just landed on the Island of Dr. Doolittle. It seemed perfect.

Stanley and I stayed up almost all night talking about art and life and whatever else came to mind. He was clearly a very intelligent, well-read man. He was a formidable businessman, trained at the Wharton School of Finance in Philadelphia, who had amassed a respectable fortune in ranching, oil and gas, and television broadcasting. His real game was TV, and he owned three ABC stations at that time. He was fond of many things, including Courvoisier and Coors beer.

The next morning, I spent a long time talking to Minnesota, explaining to him that he was in his new home, and that he was going to be OK. I really think he understood, and as I left Toad Hall bound for Denton, I felt assured that I had done everything possible to make Minnesota’s life a long one, prolonged by the fact that he was art. Stanley seemed delighted to have Minnesota, and he was making arrangements as I left to have a couple of journalists over to meet him. One of those journalists was Frank Deford.

Deford’s feature story, entitled “A Site for Tired Eyes”, appeared in, of all things, Sports Illustrated, on April 18, 1977. The story was mostly about Stanley himself, his eccentricities and strange business ventures, but it also mentioned art. In fact, Minnesota was photographed in his pen with Stanley, whose arm was in a cast as a result of a recent tumble. The caption underneath the photo mentioned winged pigs sedated with wine and massaged with baby oil so the tattoos would show up better. (The pig was growing exponentially, so the tattoo was stretching out and becoming less distinct. I had mentioned that the tattoos looked better if Minnesota was clean and oiled, thus the caption.) What was not mentioned in the caption was any reference to the artist. It appeared that the pig had flown in from parts unknown and landed in Stanley’s back forty. This “journalistic oversight” was the first in a pattern of such things in my history with Stanley Marsh, and I was beginning to get a bad feeling about Minnesota’s future as well.

I received my MFA in May, 1977, and before I even had a chance to pack up and move, I got a letter from Stanley. The letter said that Minnesota was dead, “overdosed on chocolate Easter eggs and champagne”.

Minnesota hadn’t even been at Toad Hall for two months before he was dead. To make matters worse, Stanley had him stuffed.

Saddened and disgusted, I moved back to Houston to try and make my way as a painter.

DOGS

Some of the things Stanley and I had talked about when we sat up all night drinking in his library were our plans for the future. I was about to finish my degree, and Stanley wanted to know what my next project was going to be. I told him I wanted to tattoo several hairless dogs. I was already working on different designs, but it was pretty theoretical at that point, because I had never seen a hairless dog. I had no idea what one cost, and it might generally be an expensive proposition to get the dogs, set up an operating theater with veterinary supervision, hire the tattooist, etc. I only mentioned it to Stanley because he asked. After I got the letter from Stanley telling me Minnesota was dead, I figured I’d never speak to him again.

Months passed. In Houston I got a job in a sign shop just to survive, even though I hated billboards. I was making paintings in the dining room of my apartment. I didn’t have a studio. Then one day out of the blue I got one of Stanley’s letters… in the giant-size envelope that he was known for. The letter was pretty annoying. Stanley had been to New York, and he was very pleased with himself for having had his portrait made by Richard Avedon. During the sitting, Stanley told the photographer that as soon as he got back to Texas he was going to tattoo a whole herd of hairless dogs. Stanley had written to tell me, in advance, of his plans to use my ideas.

After I closed my mouth, I sat down and wrote Stanley a letter of my own. As I recall, I pretty much told him to go piss up a rope.

Stanley’s letter about Richard Avedon had been sent to my parents’ house in Houston, since apparently he couldn’t find my address. Soon after I replied to Stanley, my parents started getting phone calls from Stanley’s office. He was looking for me, but I probably didn’t have a telephone at that point. But I was in regular contact with my parents after moving back to Houston, and during one of my visits home, I was told of Stanley’s calls. He wanted to talk to me. I refused to call him back. He had used up all his credit in my trust account, and I’d had enough. However, one day while I was visiting my folks, the phone rang, and I answered it. It was Stanley. He said that he was “sorry he had stolen my ideas”, and he wanted to commission me to do the project myself. Although I never did get a truthful explanation about what happened to Minnesota, I recognized the opportunity to do the hairless dog project. Without proper funding, it was clear by then that I would never be able to make it happen. I accepted Stanley’s offer to underwrite the project, and I began in earnest to look for the elusive naked canines.

There were two tactics that I used to locate these dogs. One was to simply look in the best-known dog magazines for breeders, and the other was to go out and find the dogs myself. The best lead I had at the time was some pretty well-documented evidence of the existence of a creature known in Mexico as xoloitzcuintl, the old Nahuatl word for “dog of the gods”. I decided to go to Mexico City and investigate.

Once in the capital city, I started looking in the phone book for “pet stores”. I made a lot of calls and came up with nothing until I talked to an old man who knew of a breeder of these legendary dogs. She was a Spanish marquesa. Actually, she was la Marquesa de Premio Real, and she lived in a four-hundred-year-old house surrounded by fifteen-foot high stone walls in the center of Mexico City. When I phoned her, I explained that I had come from the United States to find the famous Mexican Hairless Dog, and that I was interested in establishing the breed north of the border. The marquesa was very gracious, and she invited me over to see the dogs myself, at that point for the very first time. Before then, I had only seen photos. When I first laid eyes on these dogs in the marquesa’s large, pefectly-manicured back yard, I was impressed. There, gamboling on the green, were four muscular, square-headed, frisky animals, and they really were quite hairless…just a little wisp of hair on top of their heads, sort of like something Dr. Seuss would think up.They also appeared to have no teeth. I asked the marquesa about that, and she explained the genetic connection between teeth and hair. The trait for each feature is located on the same gene pair, and if the individual has no hair, he by definition has no teeth…well, very few teeth, anyway. The pups are born with all their baby teeth, but a large portion of the adult buds are never there. This apparently would also explain why the dogs were so fond of fruits, vegetables, and grain. They liked meat, but nature didn’t give them the means to catch and subdue much of that, so they were omnivorous foragers by default. The marquesa went on to tell me of the history of these dogs in Mexico. I had heard that Frida Kahlo kept them, and I had seen, in my preliminary research, ceramic renditions of fat little dogs done by Pre-columbian craftsmen, and now it started to make sense to me.

Those fat little dogs were xoloitzcuintles. The original Mexicans regarded them as sacred, but they also regarded them as dinner. The protein supply in Pre-columbian Mexico was pretty slim. There were no cattle, no horses, and no swine as we know them. The domestic animalof choice was dog, and these little animals, fattened with corn, were regular table fare. A delicacy whose recipe was passed on to the Spaniards consisted of xoloitzcuintles, gutted and stuffed with axolotes (a type of salamander once common in the lakes of Mexico City), then baked with hot rocks in a hole in the ground for several hours…the Aztec version of turkey and dressing.

I never mentioned my artistic intentions to the marquesa. Even though she had told me of the common fate of her own dogs’ ancestors, I could tell by her gentility that she would not have approved of my idea. However, she was willing to sell me a couple of her dogs. They were exquisite specimens, very healthy and happy. They would have made good pets. But the marquesa was asking a lot of money for them…too much, I thought to myself, so I told her I would think about it and let her know. I ended up declining her offer, but undaunted, I put an ad in El Heraldo de Mexico generally asking anybody for leads to these dogs. I left Stanley’s name and number in Amarillo for a contact, and I flew back to Houston, where I continued making drawings for the project.

*******

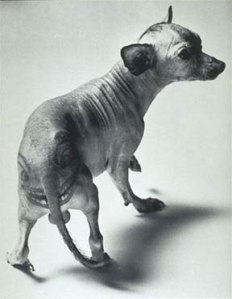

Of course we eventually got our dogs. The best dog was a little Chinese Hairless who was sold by a kennel in South Dakota and air freighted to Amarillo. I got a call from Stanley’s office describing the dog’s size and coloration: he was small, pink, and almost totally bald. He wasn’t a puppy any more…he had languished in the kennel for months, maybe even years, because he was so ugly by conventional standards. To me he sounded beautiful.

Around the same time we acquired this little Chinese Hairless, Stanley got a call from Mexico. It was a man who claimed he could get us four xoloitzcuintles. As I recall, he was asking about two hundred dollars apiece for them. On his word, I flew to Brownsville with my friend Lynn Harris, who came with me to document the trip on video. We rented a van and drove to Mexico City to meet with the man. After some haggling and driving around, we got our dogs. They were a bit scrawnier than the marquesa’s dogs, but basically they were OK. I had them all checked out by a vet and made sure they were vaccinated. Then Lynn and I drove, without sleep, from Mexico City to Amarillo. The trip itself was exhausting enough, but to make it even more interesting, a U.S. Customs official let one of the dogs out of the van when we got to Laredo, and the dog bolted in an easterly direction. After getting neither an apology nor an offer to help catch the frightened animal, I chased him on foot for what was probably a couple of miles into a little neighborhood right on the Rio Grande, where, with the help of a small boy, I cornered the runaway beast in somebody’s back yard. The dog, confused and frightened, bit the hell out of me. Drawing back my hand from his mouth, I laughed because I realized he didn’t have any teeth. So, in spite of a severe gumming, I grabbed him up, and we drove straight through to Amarillo.

After securing a number of dogs, we had also arranged for Randy Adams to fly from Ft. Worth to Amarillo to do the tattoos. A local vet was contacted, and after he got used to the idea of what could have been a marathon tattoo session in his office, he accommodated all of us. There were still some unknown factors with all this. The big unknown was simply, “What happens to tattoo ink on the skin of a smokey grey hairless dog? Does it go on opaque and visible, or does it sink in and disappear?” We really didn’t know, so we anaesthetized a xoloitzcuintl and applied the tattoo machine. To our dismay, the ink… every color…sank into the dog’s skin and totally vanished. The entire trip, two trips altogether, was a failure. The dark-skinned Mexican dogs would not be suitable for the project. They ended up adopted by people in Amarillo and Houston, never to be tattooed.

But we had an ace in the hole. His name was Hot Dog, and he was pink.

Hot Dog originally spent most of his time in Amarillo. He was commissioned by Stanley, and Stanley did own him. Stanley’s little girls were very fond of Hot Dog, and they spent a lot of time with him. They even entered him in a couple of ugly dog contests, and they were of course for Hot Dog no contest at all. He eventually retired from the contest business undefeated.

After a couple of years of being shuttled back and forth between Amarillo and Houston, Hot Dog ended up with me. At first, he spent the summers in Amarillo and the winters in Houston. It was sort of like having a kid in boarding school. One thing about old Hot Dog was that he never really took to being housebroken. He had a way of peeing in secret places all over Toad Hall, and I think maybe Wendy Marsh finally had enough of him. Years before, Stanley had undergone brain surgery that rendered his olfactory powers almost useless, so I guess he couldn’t tell what Hot Dog was up to. After Hot Dog moved in with me and Chester and Elvis, he basically behaved himself. Chester and Elvis always set a good example.

Meanwhile, I was still on the lookout for some more light-skinned hairless dogs, because we still had a bunch of designs that never got used. Over a period of a couple of years, I had sent several designs to Stanley, because the plan had originally been to do a herd of tattooed hairless dogs, all in Amarillo.

One of those designs was called The Dog With Two Different Faces in Two Different Places. I got my inspiration from Medieval and Renaissance art and also from just observing dogs’ behavior.

LITTLE FEATUS

All dogs are bipolar. I don’t mean they’re manic-depressive. I mean they have a North Pole and a South Pole. Their identity is established by both, and they recognize each other by using both. Whenever dogs greet one another, they sniff each other, north and south. Whenever they urinate or defecate, they’re not just eliminating body waste, they’re signing the neighborhood guest book. After a dog has marked a spot, other dogs who subsequently come along can sniff and tell: what gender the dog was, how big he was, what he’d been eating, and how long ago he signed in. Dogs interpret this information to know the territory because, in the last analysis, they’re social animals, and their relationship to one another is hierarchal. This hierarchy determines dominance, which determines feeding order and reproduction rights.

One day it occurred to me, while observing the hindquarters of a dog, that his tail looked like the trunk of an elephant, and his anus kind of resembled a mouth. That illusion could be very firmly reinforced if he had a great big pair of eyes to go along with these features, located in the appropriate spots.

Of course, I also remembered seeing images of the Devil in European art. Sometimes he had a face on his ass.

Obviously the image had presented itself to other artists in history when they too looked at some animal’s backside and imagined the same thing. I just gave it a slightly new twist. Randy Adams put Featus’ second face on him in 1982 at Dr. Fussell’s office in Houston.

ARTEMIS

After Minnesota, I didn’t want to try another tattooed pig. It might sound naive, but a lot of the motivation behind my decision to tattoo a pig was to annoint him with a mark that would render him impervious to the fate of all pigs. I was hoping Minnesota’s tattoos would make him like Achilles dipped in the river Styx by his mother…invulnerable.

In 1984 I got a call from my friend and former professor, Bob Wade, who was living in Santa Fe at the time. Bob had been talking to a man about the Minnesota project, and the guy was apparently completely taken with the idea. His name was Ralph. Ralph telephoned me soon after talking to Bob, and he asked me to tattoo another pig. I didn’t really want to do it at first. I had already done it once, and that was enough, I thought. But then, as Ralph kept talking, I saw another opportunity…perhaps to try to immortalize another pig, and perhaps to really do a pig project without the constraints that I had encountered in graduate school, not the least of which was a low budget. Ralph offered me a reasonable fee to do the project, which this time cost one hundred dollars an hour for the tattooist and another pretty sizeable amount for the operating theater. Randy Adams was not available for this session, but I had met a very capable tattooist in Houston in the mean time named John Stuckey, so I booked him and his assistant. I made arrangements with Hot Dog and Featus’ regular vet, Dr. Richard Fussell, to oversee the clinical aspects of the work, and I found a beautiful young Chester White pig in Bryan, Texas. I named her Artemis, after the archaic statues of Artemis found at Ephesus, with the multiplicities of breasts. Artemis was a young sow, and I was really impressed with the number of nipples she had. It looked like she could nurse a small crowd of piglets when she grew up.

Ralph wanted a tattooed pig as a present to give to his favorite uncle, whose seventieth birthday was just a few weeks away. I had to work with that timetable in mind, but it wasn’t really a problem. What might have been a problem was that Ralph’s uncle lived in California…Beverly Hills, as a matter of fact. I didn’t really want to drive Artemis to L.A., so Ralph said he would arrange for his private plane from Santa Fe to pick us up when the time came. I actually finished the work ahead of schedule, so Artemis lived illegally in the city with Hot Dog and Featus and me for a few weeks. She was a very smart animal who had no trouble whatsoever in adjusting to life as a yard pig. My neighbors didn’t mind her at all, either. I remember the little boy who lived next door, looking through the fence at Artemis and giggling to his mother, “Mira, mira, el puerco tiene alas!”

A PIG FLIES, OR, SWINE BEFORE PEARLS

The day came when it was time for Artemis to fly to her final destination. Comfortably confined in a large portable dog kennel, she rode in the cabin of the aircraft with me, first to Santa Fe, where we met Ralph, and then on to Los Angeles. During the flight, Ralph explained more to me about his uncle. The man had been a Republican congressman from the district that included Beverly Hills and was now retired. The congressman’s seventieth birthday party was being given by some friends at a posh Beverly Hills residence, and Ralph wanted to present Artemis to him in a grand manner, arriving at this party in a limousine. That’s just what we did: Ralph, Artemis, and I showed up in a stretch limo to much fanfare and general amusement.

The humans were amused, but Artemis was not. She made her entrance into society alright, but, like me, she didn’t like crowds. Just a few minutes into the party, I rescued a very confused Artemis and put her in her kennel in a quiet place outside of the house. As soon as she was back in her familiar, safe kennel, I brought her some hors d’oeuvres and salad. She settled down pretty quickly, so I went in to join the festivities, intending to check in on her from time to time during the evening.

The site of this birthday soiree was a very comfortable home in the heart of Beverly Hills. It was well-appointed and tastefully furnished with silk wall coverings and the largest, most beautiful Chinese rug I had ever seen. The hostess, while exhibiting a tolerant sense of humor regarding Artemis’ presence, was understandably nervous with a pig running around loose in her house. She was relieved when I whisked Artemis to safety in her kennel and out of harm’s way.

The food and drink at the party were beautifully laid out. A huge buffet took up the entire the dining room, and the bar was on the patio out back near the pool. All the refreshments were handled by caterers dressed in white. The caterers were appalled to see a pig in the house, whether the guests thought it was funny or not. After Artemis was safely removed from the house, they too breathed a sigh of relief and went about their business.

As the evening progressed, the predictably drunk began to make themselves known. One of them was a fellow who turned out to be one of Ralph’s nephews. I could tell that even sober he was not a regular rocket scientist. Drunk, he should have been institutionalized. The fellow announced to me that he wanted to let the pig out and join the party. I told him that it was not a good idea. He insisted. I said no. The hostess herself finally accompanied him when he asked again, so, against my better judgement, I let Artemis out. I instructed everyone to just let her explore, and I insisted that picking up the pig was not to be done under any circumstances, except by me.

Upon being released from her kennel, Artemis did fine at first. The partygoers kept their distance as she sniffed her way around the swimming pool and onto the patio. But then she decided to go back into the house. By the time she made it inside, a condition of mutual distrust was re-established between pig and people, and Ralph’s nephew decided to chase Artemis through the length and breadth of that silk-lined house with the beautiful Chinese rug.

Anybody who’s ever been to a real rodeo (that’s RO-dee-o, not ro-DAY-o) has seen a greased pig contest. Artemis wasn’t greased for the occasion that night, but she was still fast and plenty slippery. And she was sober, which made her twice as clever as Ralph’s nephew. Back and forth among the revelers ran Artemis and nephew boy, with me yelling by then at the top of my lungs for him to stop. The guy never listened, because at that point he seemed intent on proving just who had the brains in that outfit.

Young pigs only have three ways to defend themselves. The first way is to run. The second way is to squeal. A pig can let out a sound so loud and piercing that it would unnerve anybody, especially if he had never heard that sound before.

The third defense mechanism is used only in extreme situations, as a method of last resort.

After being chased through the crowd, over the Chinese rug, and around all the furniture, Artemis remembered how she got inside in the first place and made a bee-line for the open sliding glass door in the dining room, where all the food was laid out. Just as she was about to make her escape, Ralph’s nephew caught up with her and picked her up, head-in and ass-out. This was when Artemis used a combination of the second defense mechanism and the third, which was to open wide her little anal sphincter, take a deep breath, and squeeze. With a screeching Artemis in his arms, Ralph’s nephew machine-gunned the buffet, the silk-covered walls, the caterers, and several well-dressed guests. It was a regular St. Valentine’s Day Massacre.

That’s one way to clear a room. Actually it pretty well cleared the house.

After the party I took Artemis down the road to another Beverly Hills address, where she was ensconced in a large dog run, originally constructed for the owner’s prize bird dogs, but now vacant. I got Artemis some food and water, apologized to her, and once she was secured, I went back to my hotel for what was left of the night.

I had a flight booked out of L.A. the next day, and I figured I might never see Artemis for some time. The morning I left, I sat in her dog run with her, scratched her chin, and told her she was going to be alright. Ralph had promised me that Artemis would grow up to be a pet on his uncle’s ranch back in New Mexico. We shook hands on it. I got on the plane with Ralph’s assurance that Artemis would be safe. That was the last time I ever saw her.

Bob Wade told me in a phone conversation some weeks later that the congressman never really liked Ralph’s birthday gift. In fact, the congressman thought she was disgusting, so he had Artemis butchered at a slaughterhouse somewhere in in Los Angeles.

WHAT REMAINS

After the loss of Artemis, I realized the only way I could ever successfully do a pig project was to buy a house in the country and keep the pigs myself. After trusting people twice with my tattooed pigs, I resolved never to do it again. I realize now that most people simply do not think of pigs the same way I do. It’s still difficult for me to understand how the personalities of Artemis and Minnesota did not shine through to the humans who promised to be responsible for them. A photograph of Artemis taken by Mark Green was published as a postcard in 1985 and distributed world-wide for several years by Fotofolio, Inc. in New York. I got a few letters from people about her. Nobody ever seemed upset about the tattoos. Most people just wanted to know where Artemis was now, how big she was, that sort of thing. I always wrote back and said she was a fat, happy pig who lived in Hollywood, thought she was a dog, and had been trained to go get the newspaper every morning.

Hot Dog and Featus lived with me until the late 1980’s, when they both died of old age. Each was of indeterminant age when we bought him. Neither had papers, so I think the kennels who originally had them fudged a little about their ages. Hot Dog and Featus are buried underneath a big ash tree in the back yard of my former home in Houston.

Today I still have mixed feelings about the way things turned out. Obviously, I regret the premature death of both of my pigs. I am grateful to Stanley Marsh for having had the sense of humor to sponsor the tattooed dog projects. My gratitude is tempered, however, by memories of Stanley who often, when discussing either Minnesota or Hot Dog, didn’t bother to mention me as the artist.

Besides the article in Sports Illustrated, the most egregious omission was on network television. In 1979, the Today show on NBC television ran a fairly substantial story on Stanley and his eccentric ways. Part of those eccentricities included Minnesota, who by then was dead and stuffed, and Hot Dog, who was very much alive. In addition, prominently featured were four or five of my drawings, with Stanley narrating over them, explaining my ideas for future dog tattoos. The reporter, in an overdub, referred to me simply as “one man…with a whole lot of plans…” Hmmm. At least they got my gender right.

I never knew in that case whether it was just sloppy journalism or Stanley’s deliberate omission of my name. Common courtesy and common sense would suggest that whenever a work of art is mentioned, the name of the artist is also included. It’s actually part of of the copyright law as well. I don’t believe I should ever have been put in the position of insisting that this courtesy be extended to me when my work was mentioned in the press. More often than not, my objections were ignored. I often felt that the issue of authorship was a problem for Stanley, and I regret our friction over something that didn’t have to happen in the first place.

That was years ago, however, and I have forgiven Stanley and all other parties concerned. I welcome the chance here and now to simply state my own chronology and history of these projects. Over the years, the tattooed animals, especially the pigs, have more or less become folkloric or anonymously ubiquitous . That’s OK, but I still want people to know the story as I choose to tell it now.

I was happy to have been interviewed about the pigs by Susie Kalil in the Spring, 2000 edition of ArtLies, and that interview prompted me to consider publishing the whole story. It was then that I decided to add this story to my website.

Thank you for visiting,

Summer 2002

Update: July 2014: This story was originally part of my website at http://www.andyfeehan.com

I would also like to express gratitude to Fareed Kaviani for writing a short piece about tattooed pigs and the trouble I have encountered regarding Wim Delvoye’s tattooed pigs, which are obviously derivative and intended for commercial use. http://modernfarmer.com/2014/05/o-inked/

Update: April 2018: Here are two videos shot originally on Super8 film by my MFA classmate Carl Finch, in Denton, Texas, in spring 1977:

Here is the Today Show, where Stanley Marsh pretends my work just flew in and landed in his lap, anonymously, for his general publicity.

Recently my friend Hannah Smith published a blog about how she and her husband Sam rescued Minnesota’s remains from Stanley Marsh, how they found out where he came from, and how they returned what was left of him to me. I was touched by what they did.

I think this is a great article and a wonderful idea… I have had 2 chihuahua’s (Daisy and Ipper) Ipper died a couple of years ago but Daisy is very alive.

I rescued Ipper from a crack house .

I started trying to find out as much as I could about Breed.. it seems the Mayans thought they were soul guides and buried them when they died with themselves to guide them to the other side.

They have guided me indeed !

LikeLike

Andy, thank you for sharing. I am saddened with the demise of your wonderful pigs. I remember hearing about Minnesota’s tatoo from Betsy way back when, but it was interesting to hear the whole story. I would say that Stanley Marsh is a pig, but that would be an insult to the animal.

LikeLike

Hi Kathy. Thank you for your kind remarks, and thank you for taking the time to read the whole thing.

LikeLike